Methodology

Twenty-seven organizations responded to our invitation to share cases for MeasureD, with a total of 31 projects submitted for review. We conducted interviews with all submitting parties, identified 12 projects for further investigation, and chose eight for inclusion. The criteria used for selection is outlined in the About section of this site: we looked for evidence that the social design process was deployed for a significant portion of the initiative; that the overall goal addressed either cultural or behavioral determinants of health, or clinical health; that objectives for the initiatives included behavior change or systems change; that measurement was used; and that access to participants and documentation made it possible to create a full enough picture to serve as a useful example. All original case submissions can be viewed here.

This was not a traditional case study methodology that posed research propositions and then investigated them through data collection. Rather, we conducted these cases to describe and explore the use of social design in social impact interventions and the integration of measurement into this practice. We learned, from conversations that took place at the MeasureD Symposium in 2017 and from discussions in our varied peer networks since then, that design’s influence on health and the roles measurement plays in it have not been fully investigated, documented or understood. Thus, we set out with multiple goals: to uncover the ways in which design’s contribution is currently evaluated and the roles measurement plays in design-influenced social programming; to capture learning to date; and to posit the ways in which measurement can be used to make design, in the context of social sector programs, more effective.

We conducted extensive interviews with multiple participants in each of the projects featured here; with designers, funders, implementers, internal and external evaluators. We reviewed the documents and documentation supplied, as well as any ancillary materials available. Content appearing on this site has been reviewed and approved by the individuals and organizations that submitted it.

Much of our own learning through this process has resulted from making the tacit knowledge and assumptions of the two very different disciplines we represent — design and evaluation — explicit. We discovered, through our conversations, differences as well as parallels in language and perspective that became evident only because we needed to rationalize them in order to understand what we were seeing. These investigations of our distinct mindsets were not only useful to us in representing the work included here from a more holistic perspective, but we also believe they have contributed to a more complete picture of the different (and similar) ways designers and evaluators think, speak and practice.

The original call for cases included these questions, in addition to a brief description of the health challenge the initiative addressed, and the ecosystem in which the work took place.

- When was it begun and completed?

- What was the intent of the social design?

- Please describe the intervention with a theory of change.

- What steps were taken and what methods were used to track outputs and outcomes of the social design phase of the process?

- What steps were taken and what methods were used to track outputs and outcomes of the social impact intervention?

- What lessons did you learn from this particular experience?

Additional questions guided further investigation of the cases.

- What was the process used? Not just what happened, but how did it happen? Specifically, what were the step-by-step design and measurement activities that took place? What was learned, and how did that learning change subsequent activities and decisions?

- Who was involved, and when, during the overall process? What difference did it make?

- How was the team structured, and what impact did that have on the design, the evaluation, and the sustainability of the project?

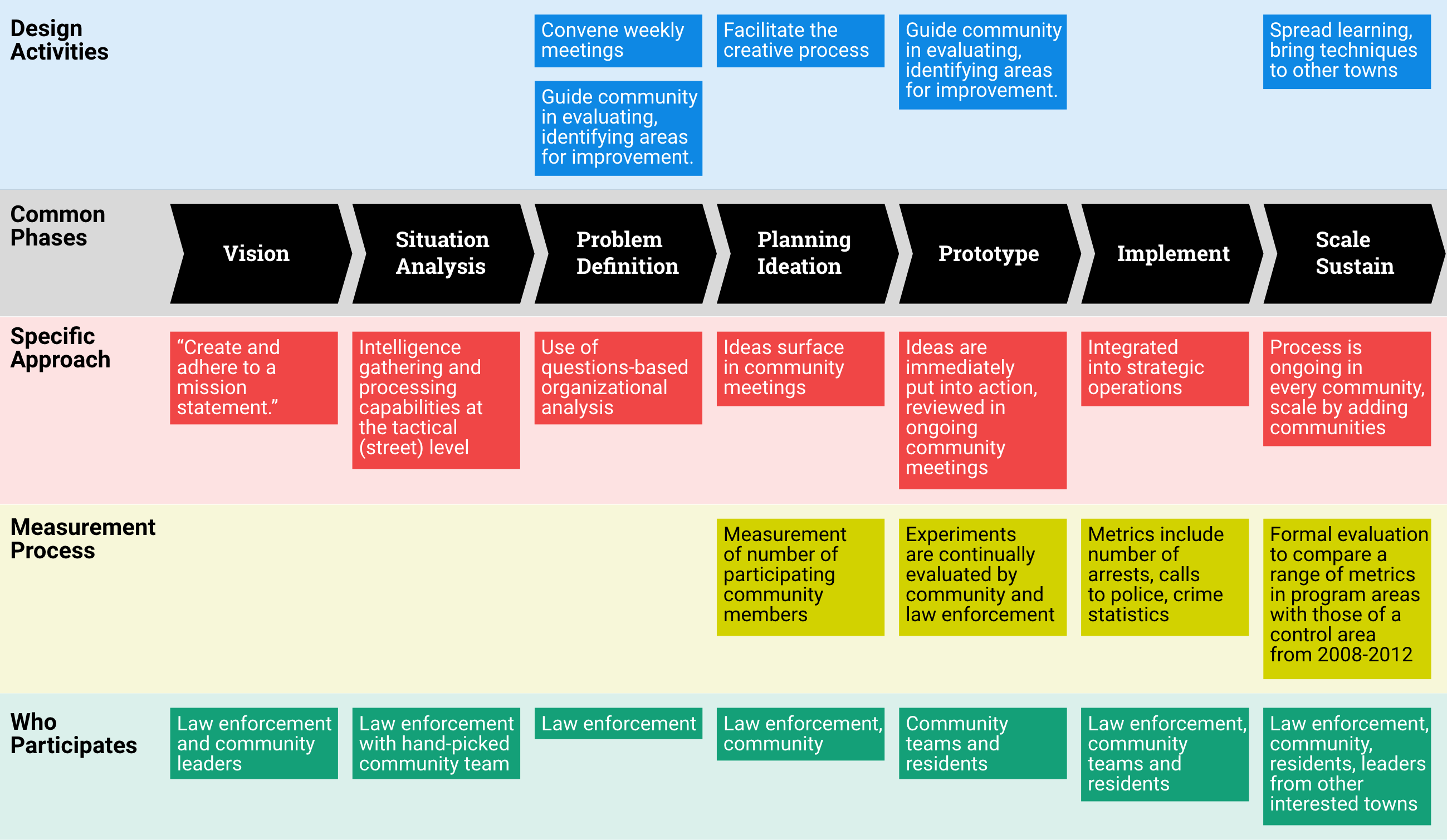

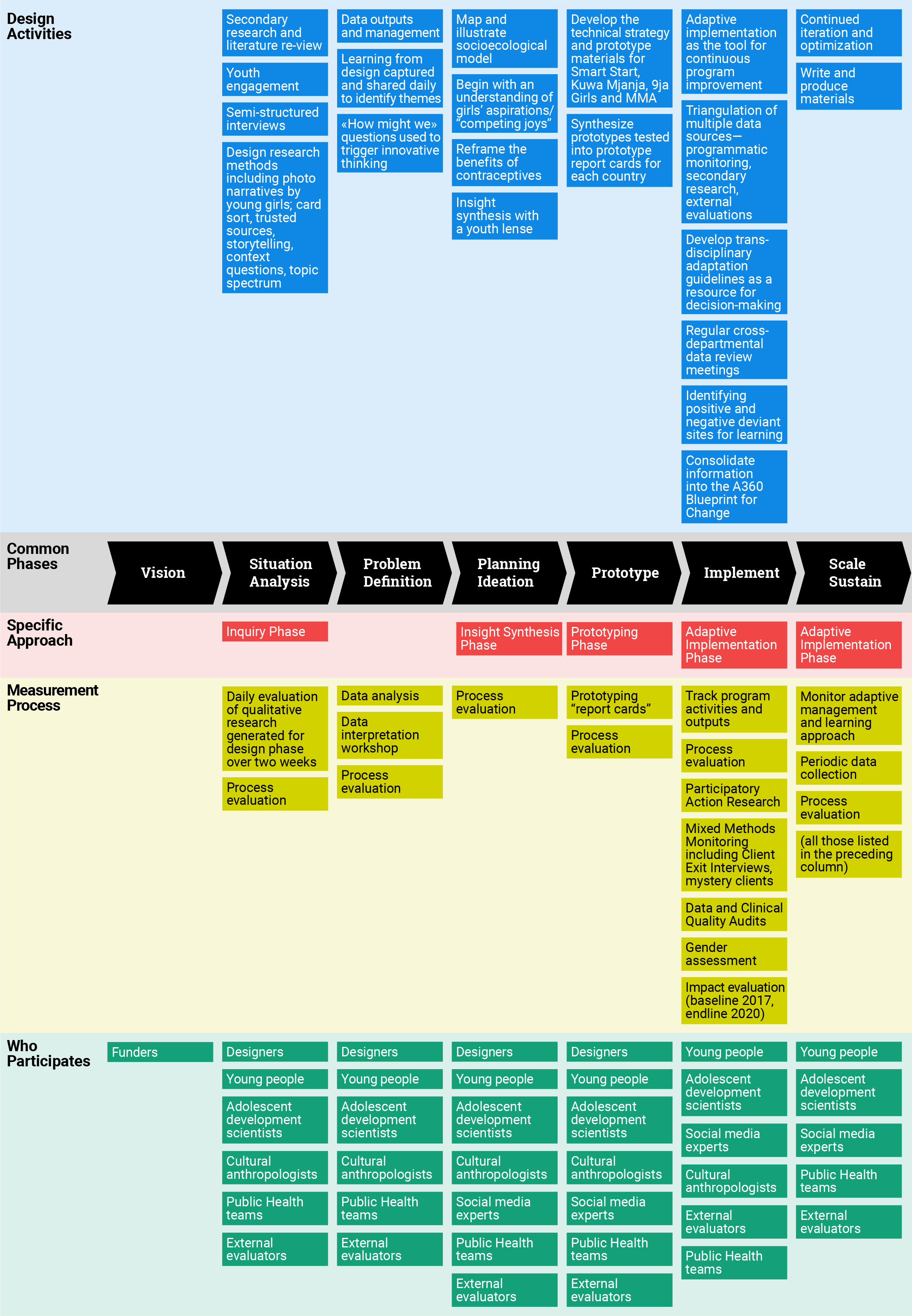

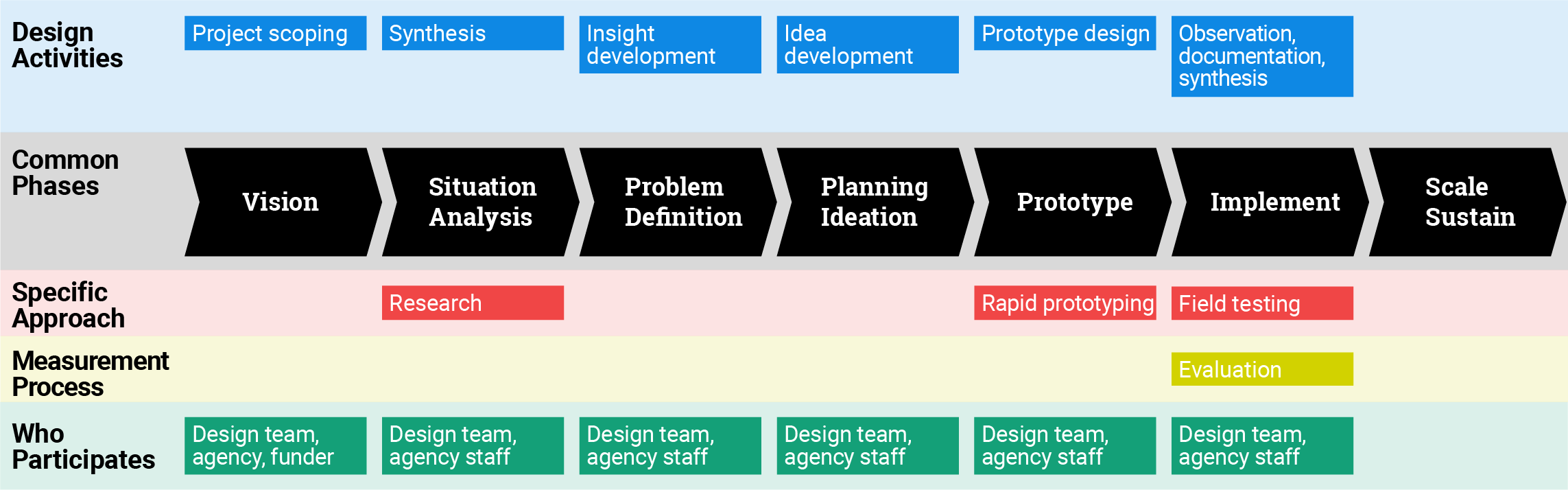

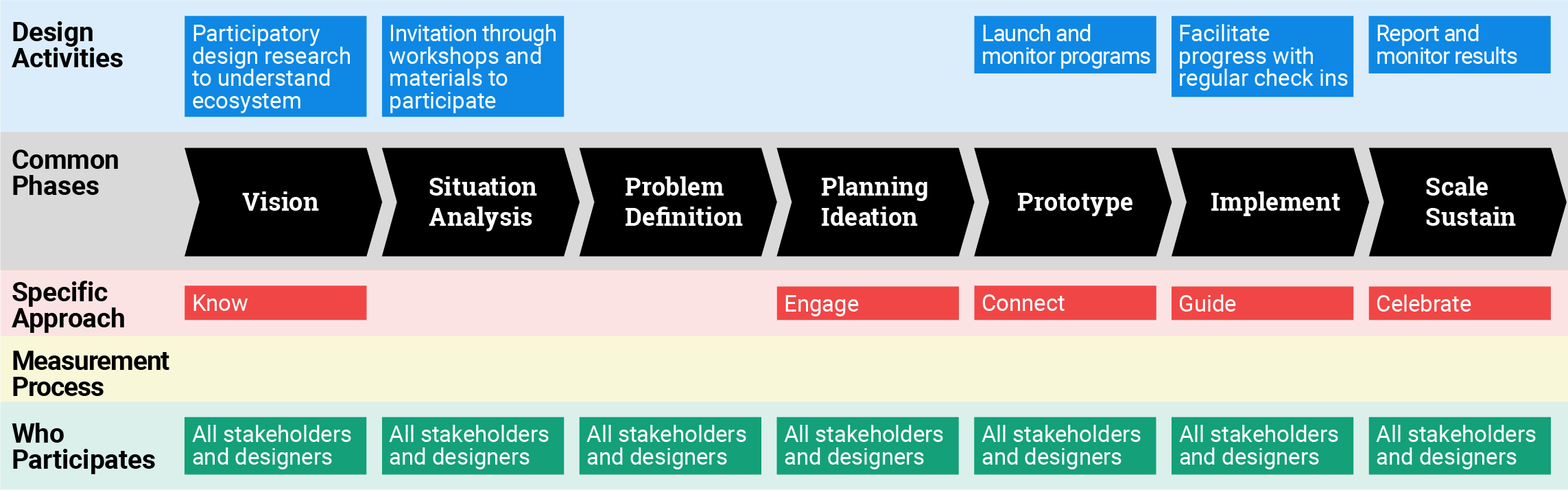

- What were the common, underlying process phases, regardless of the terminology used to describe them? And what were the differences in process from case to case?

- What were the outcomes, not only at the culmination of an initiative, but along the way? What was being measured and what was being learned?

Overall Learning

-

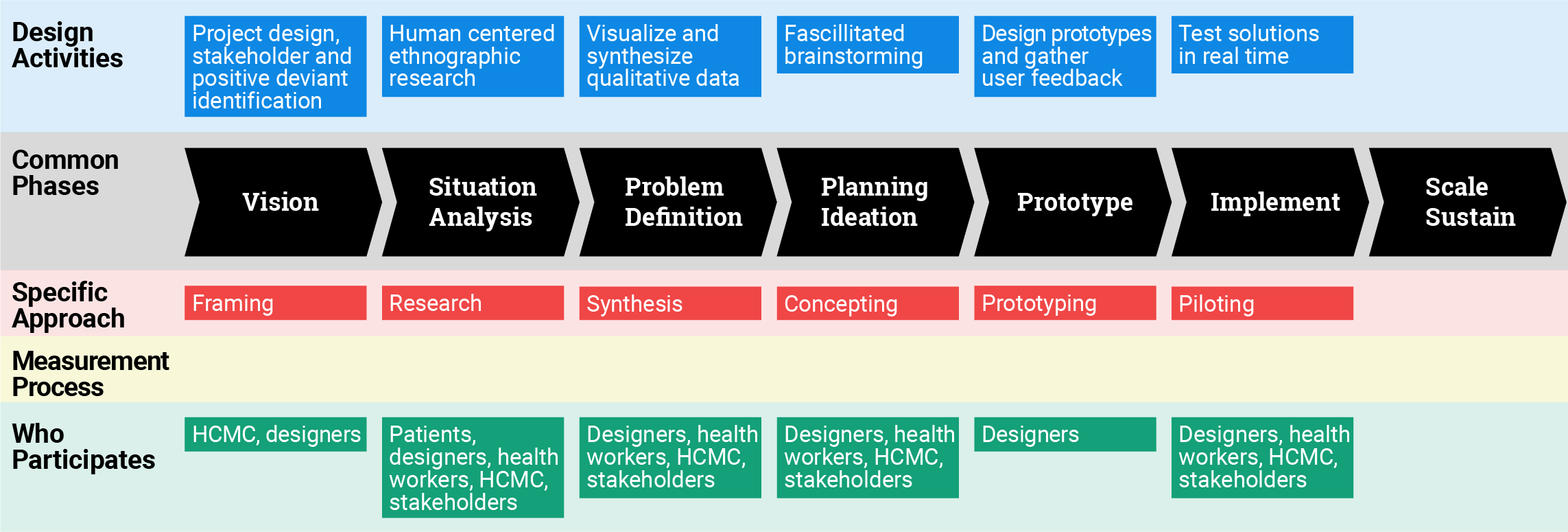

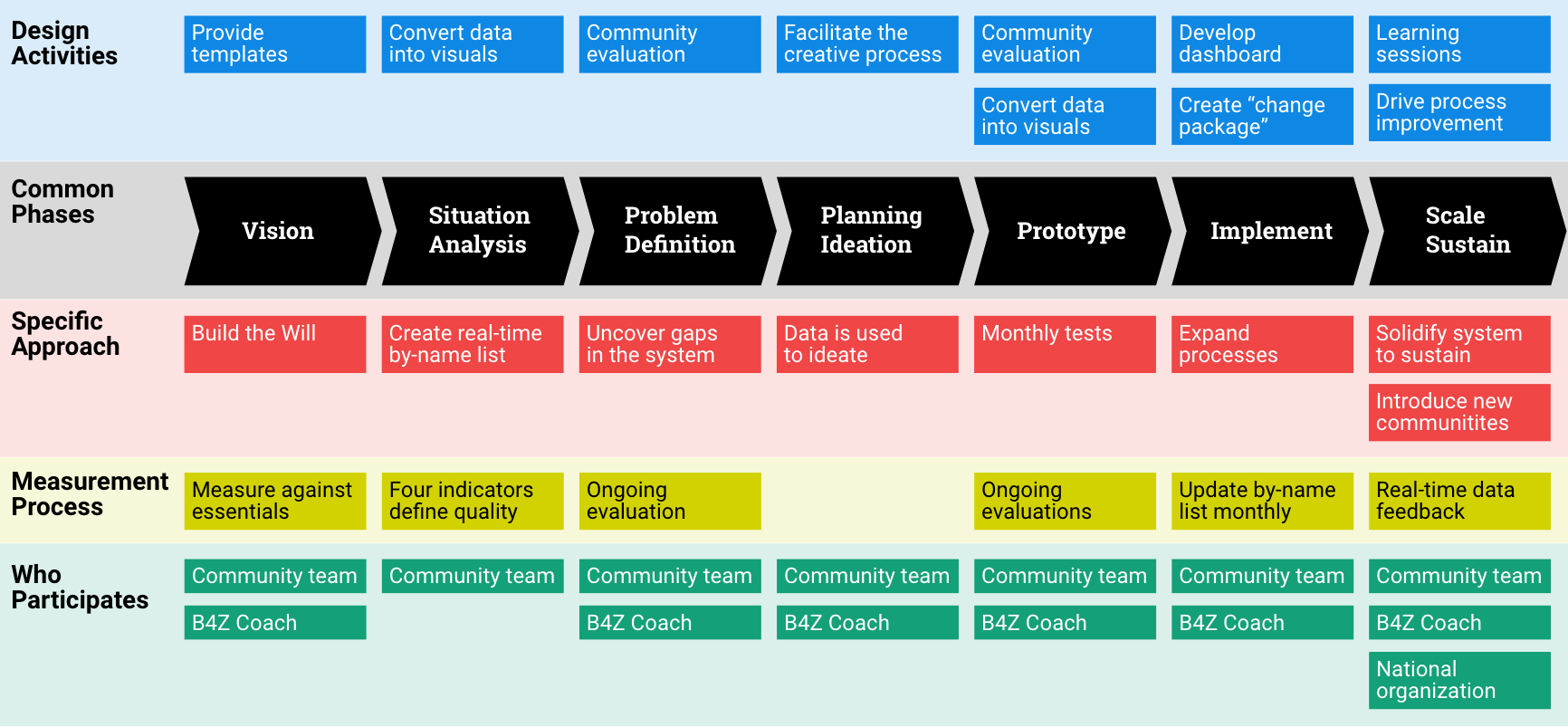

The “design process” is deployed in many places, with various names. It has a common set of stages and principles, some of which are new to public health and social impact programming, while others are not. This common methodology is the one used in the main graphic for each case.

In addition to the unexpected example of law enforcement, design methodologies are similar to adaptive management, the lean start up method of business development, the agile development process, and many “human centered” approaches to understanding end-users in order to develop more relevant services and products. Design is distinct from these other methodologies in that its broad, systematic approach spans research, synthesis, idea development, problem reframing, prototyping, and implementation, providing tools and processes for each stage and packaging them in a cohesive process.

-

Despite the important role that communication plays in the practice of social design, we do not yet have a shared language to facilitate the requisite collaboration. Often, different words are used to label similar activities and stakeholder groups. Human-centered design, patient-centered design, user-centered design, evidence-based design, and impact design are used in different context to mean essentially the same thing. Stakeholder, end user, customer, target group, community are labels that benefit from more specificity than they are sometimes given.

Words are frequently used interchangeably for activities that are not the same, like prototype, pilot and sprint. Jargon and generalities are used as short-hand for complex concepts describing implementation, outcomes, and scale, with dangerous assumptions about their clarity. Often, different disciplines use the same words to mean very different things, such as “research” or “impact,” and each claims unique ownership of the “correct” meaning. A scientist in a well-known research hospital said that designers there are “not allowed” to use the word “research,” because only scientific research can be considered rigorous. At the very least, contextual variances in what is meant by a word from one discipline to the next need to be recognized.

In some instances, we have a surfeit of words, for example, when consultants invent neologisms to “brand” their process or a part of it (an example is “Verbal Design,” which implies that other design processes don’t include language), adding to the vocabulary in the field as well as the confusion. In other cases, we lack words for essential components, for instance, we have no words to describe the types of information and feedback that designers register throughout the process in order to guide and refine it — evidence that is real but not often counted or countable.

A glossary of terms found in all submitted cases can be found here.

- Measurement and evaluation of evidence is an essential activity applied throughout the design process. Expert designers develop a body of experience and knowledge, which they use to make decisions, recognize opportunities and understand the contextual subtleties that impact outcomes. While there are “rules” for the design process that can be taught, the tacit knowledge of expert designers, while difficult to unpack, is no less real because of that. The nature of the design process is that it depends upon almost constant feedback and evaluation of the evidence uncovered. “Noticing,” recognizing patterns and connections, looking without judgment or preconceived opinion, and paying attention to what is missing as well as what is present are some of the key skills of an expert designer, as is rapidly integrating what is noticed. Shifting contexts and dynamics are synthesized into either subtle or radical changes in direction, whether these changes take place in a collaborative work session, or as reactions to a prototype that prompts refinement in real time. Good design inevitably has a set of criteria against which the design activities are evaluated.

- This “evidence” that the design process produces has been, to a large extent, invisible to non-designers, for several reasons. Due to the fact that it is tacit knowledge, it is by nature difficult to put into words. For the same reason, there has been no common language for understanding how design techniques integrate “measurement.” Finally, it is not common practice for designers to make their evidence-collection and analysis methods explicit, because so much emphasis has been put on evaluating the final product or result of the design process, and not the quality of the process itself. Even design educators recognize the need to formalize the types of decision making, observation and measurement that the expert designer develops and uses while designing. (Lawson, Dorst, 2009)

- The long term effect of the design process, and perhaps one of the most important, is that participation in it builds capacity within teams or communities for observation, human-centered approaches to learning, problem reframing, ideation, prototyping, collaboration, and iteration. This effect can be seen in the work of Built for Zero and C3 most directly, but it was a dynamic mentioned anecdotally in every case studied. This is an important observation, and one that supports the investment in and application of the design process. When done well, it creates agency among stakeholders to continue to find solutions to shared problems. A challenge in traditional social sector programs is that often, monitoring and evaluation stops at the conclusion of a particular intervention, focusing on intervention effectiveness. It can, in some cases, focus on the measurement of community capacity to apply the intervention in other settings but it does not necessarily assess the ability of communities to take a human-centered, design-led problem-solving approach to address future challenges.

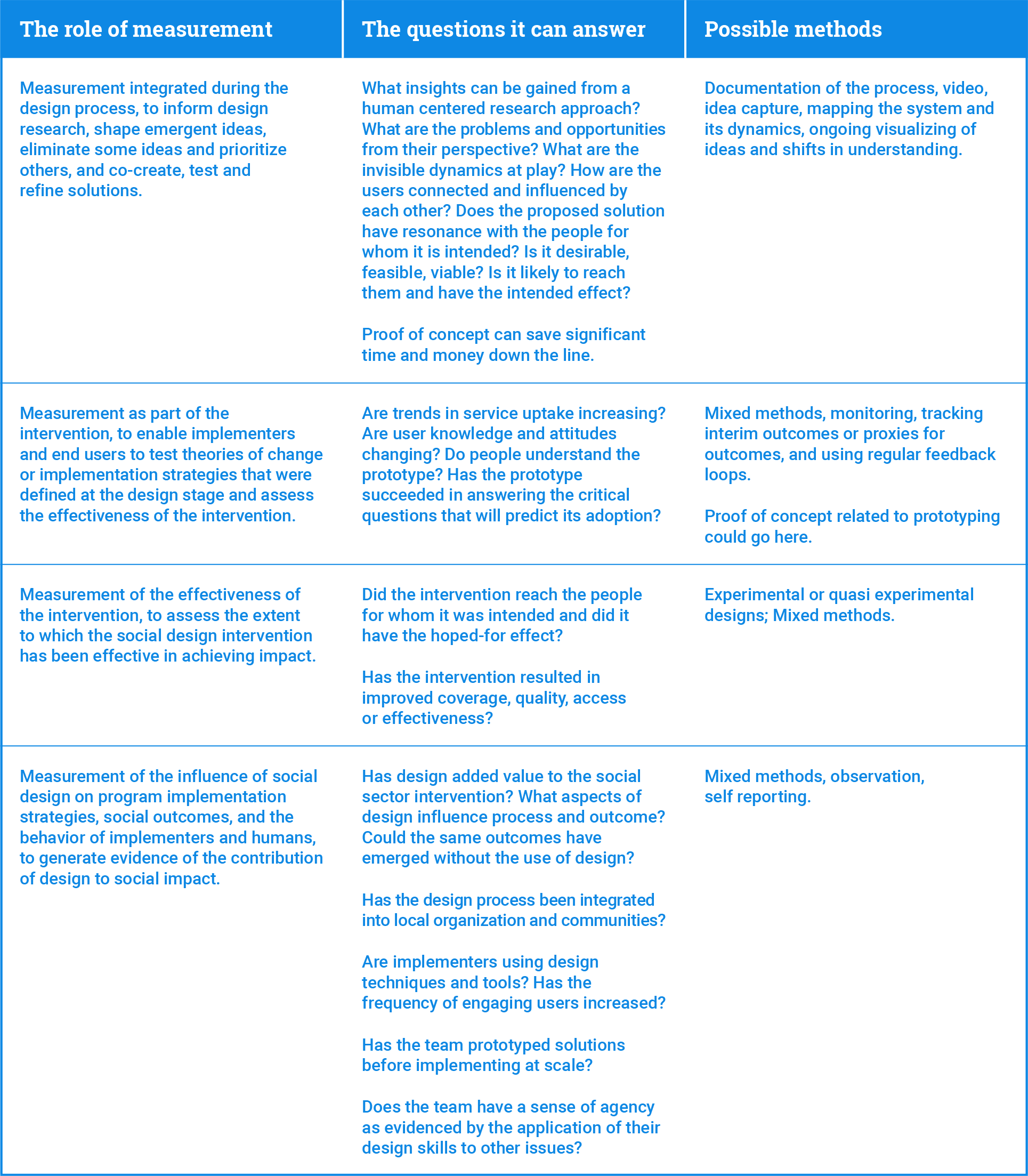

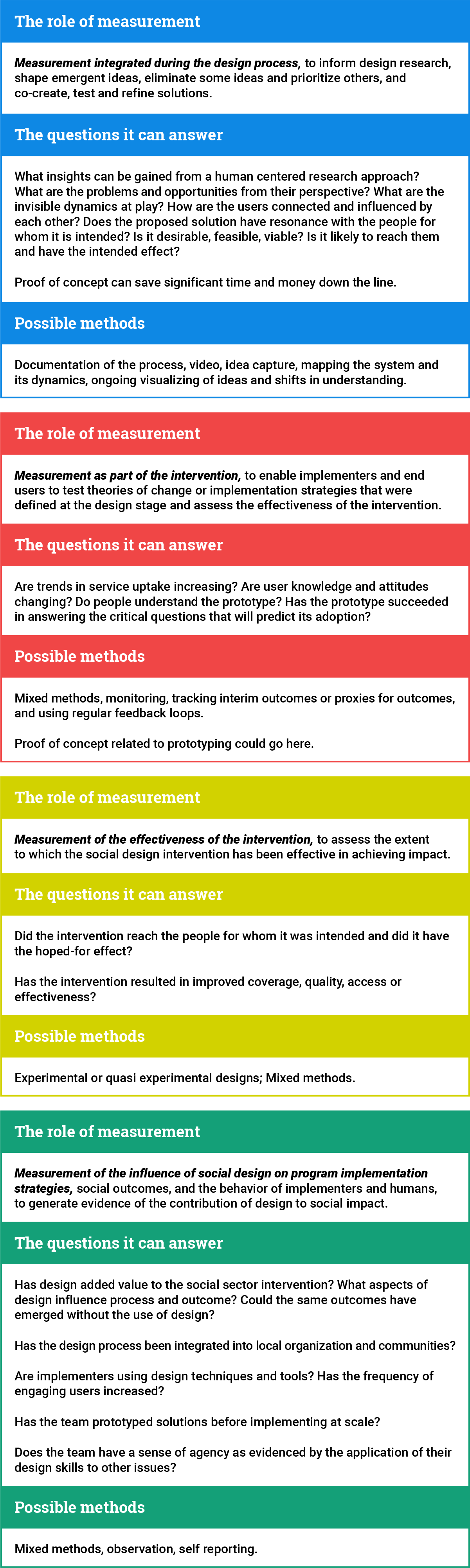

- The value of integrating measurement into design comes from its role in making the outcomes we seek in the context of program intervention explicit, defining hypothetical pathways and drivers that lead to these outcomes (e.g., through a theory of change), and providing subjective and objective metrics to test the pathways over time, to help determine whether the intervention is creating relevant conditions critical to its overall success. The challenge for design-led implementers is to determine what kind of measurement is relevant at what stage of the design-implementation process.

- No one is measuring the impact of design alone. With the exception of A360, they are mainly measuring the effect of the intervention, not the influence of design on the outcomes. This is perhaps because design is fully embedded as an implementation strategy, which makes it difficult to tease out its effect.

- There is value to be derived from studying projects before they are complete, due to the benefit of iterative evaluation and the opportunity it provides for refinement and course correction along the way. In the cases studied to date, there was much to be learned from projects that have yet to reach their final goal (e.g., sustained low crime rates; well-nourished children).

- The elephant in the room is that measurement costs money and often comes as an afterthought rather than as part of program design and performance improvement. That conversation should not be avoided. It’s important to be more aware, and more explicit about which parts of the process inherently include measurement, and which aspects do not, and need evaluation. For funders, designers and implementers serious about outcomes and assessing pathways to outcomes, it is necessary to develop an intentional approach. The lesson is that measurement, just like design, needs to be a considered, ongoing effort at all stages of program implementation — and beyond, to understand the lasting effects.

- In the design process, the hypothesis changes as the project evolves. This requires a fluid approach to measurement, which cannot only use fixed metrics, but must be flexible and adaptive. It is not always just looking back and counting what happened, but rather learning how to use data to help people think and problem solve along the way. This adaptive approach requires measurement that is quick, grounded in studying or uncovering hypothesized pathways of change while assuring rigor and utility.

- Frustration can result when there is an expectation for types and specificity of data that cannot be known during the design phase being evaluated. For example, in early immersion and research with users, it is not always possible to derive meaningful quantitative data. What can be learned, however, is often critical feedback on whether a “problem,” as defined by public health experts and designers is relevant to users. While this is a “low data” phase in terms of measurement, it is a high value phase in terms of potential cost savings and relevance of the work to come.

A Working Framework for What, Why, and How to Measure with Design

Below is an overview of the roles that measurement plays along the continuum of the design process, the value it provides in the form of questions it can answer, and possible methods for measuring for each role.

Individual Cases

While diversity and relevance among the chosen projects were an important selection criteria, the unique lessons of each example were discovered only after much investigation.

Built for Zero

The more deeply one studies the work of the Built for Zero team and communities, the more impressive it becomes, not only because of the intelligence and effectiveness of their approach but also because they keep improving. A recent podcast, hosted by Malcolm Gladwell, “shares the story of how Built for Zero communities are defying old assumptions and showing that homelessness is a solvable problem.”

The brilliance of Built for Zero is the way they have embraced the use of data as an integral component of their process. Active measurement, requiring constant vigilance, keeps seventy-four (and counting) communities across the United States focused on the same North Star—functional zero Veteran and chronic homelessness—accomplished by empowering communities and their citizens with actionable data. These common indicators, shared among all communities on the Built for Zero dashboard, are used to keep the work on track, getting relevant information out in a timely way. They are also used to set a real context that becomes the basis for innovation in addressing the issues uncovered. Communities are taught to use the design process to develop ideas and solve problems, based on these real-time metrics and measured against them. The dashboard provides a picture of progress at the community level and also shows a comparison to the rest of the country at a meta level.

C3 Policing, the Trinity Project

One surprising lesson from this case is that counter-insurgency techniques, developed by the Army Special Forces, and social design are actually similar approaches using different language. Instead of the traditional law enforcement approach to ending gang and drug related violence, which is to arrest the criminals, the C3 approach works from inside the community to strengthen it, using human-centered research, co-creating solutions, prototyping and building will and capacity among residents to take back their neighborhoods.

C3’s prototypes are not fancy storyboards or user interfaces. Instead, they are experiments, with people, like a “walking school bus” a community escort that gets children to school safely in neighborhoods that were too dangerous for them to walk alone. Yet they solve the same purpose as the more familiar tools designers use: they provide real time feedback on the viability of an idea so that it can be modified and refined in use.

C3 measures the effect their work is having in three ways. In weekly community meetings, every issue, from near-arrests to a broken street lamp on a dangerous corner is surfaced and discussed; the number and types of crime are recorded regularly in public police records, and a long-term study investigated other indicators of community health like real estate prices, and the amount of graffiti (an indicator of gang activity).

Adolescents 360

A360 is the most “examined” case included here. It is the only instance where the objective of measurement was to understand whether a design approach improved outcomes, in this case improved uptake of reproductive health services among adolescent girls. The implementers and the evaluators followed the whole of the intervention: baseline, midline and endline, monitored how the process was working, and how the way the process was being implemented was affecting the intervention and the outcome. The design, implementation and measurement teams worked closely together to understand and learn how to integrate design, global health practice and measurement in effective ways and are actively sharing their learning here and through journal articles.

Connecting Families to Public Benefits

A relatively small project, and one that has yet to be completed, this case includes an interesting insight, however, that is relevant to any organization susceptible to unexpected budget and direction changes. Chelsea Mauldin, Executive Director of the Public Policy Lab, has developed a method for including a “proof of concept” at the end of each design phase. In this way, even if the project is paused, a case for its potential effectiveness has been documented. This makes it more likely to be continued, and also means that, even if the direction is changed due to external circumstances, the new direction benefits from learning accrued.

Fitwits

Kristen Hughes, the designer behind Fitwits, believes that the strength of the program is due to her training as a communication designer. Its inception was an assignment, from a group of doctors, to “fix” a failing interface intended to entice children to record what they ate. It was Kristen’s “children-centered” approach that uncovered the potential to go beyond recording consumption, but open up a world of potential to engage young people, their teachers and families in a gamified program to not only increase their understanding of the role food plays in health, but to make them champions of change in their classes and home lives. Hughes believes that another aspect critical to the enormous traction the program garnered was the luxury of time, to build understanding and trust, throughout the ecosystem of stakeholders involved. A key lesson is that this designer-founded and led project did not build a sustainable business model into its design from the start, and was never able to successfully separate from the university where it lived to become a stand-alone organization.

MomConnect

In this case, design research, and its consideration of the agency and needs of every stakeholder, was the impetus for the project’s expansion — from a more efficient method for recording pregnancies — to a robust suite of mobile technologies fostering supportive dialog with mothers to improve their health. It is an excellent example of how social design, in tandem with technology, can address the human dynamics that make new technologies successful.

Hennepin County

This project shifted the perspective, and the strategy, of the Hennepin County Medical Center to a “journey-based” model of care where the health of complex patients (those with co-morbid conditions) is viewed not as an end-goal, but as a journey, along which patients can be moved toward better care in incremental steps. Geographically contained in one county in Minnesota, and focused on a specific patient group, the case provides insights into a deep and thorough process with application at larger scale.