What is Social Design?

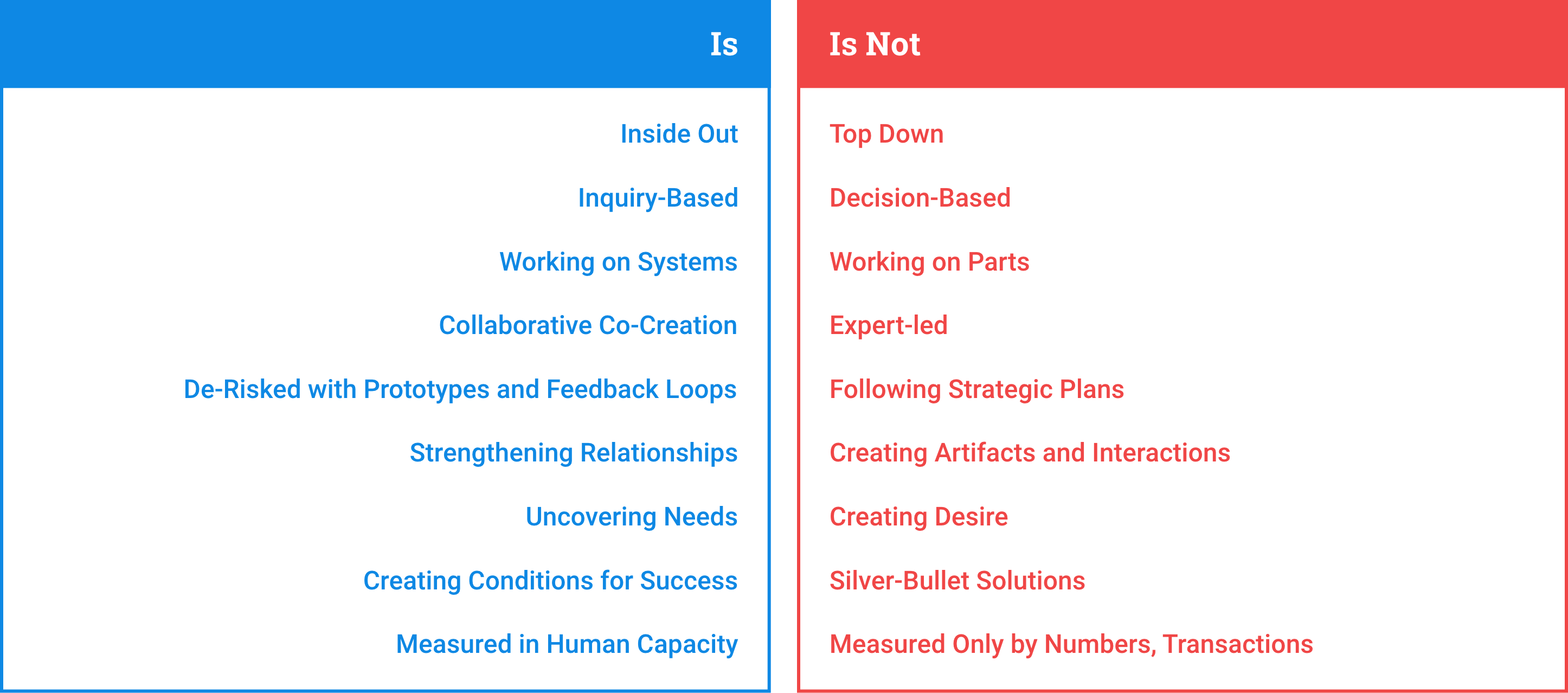

We use the term social design as the name for a broad practice that includes Design Thinking and has human-centered design (HCD) as one of its core principles.

Design has been defined as “the creation of something according to a plan.” In traditional contexts, that “something” has typically been a product, service, built environment, information system, infrastructure, or technology intended to serve a specific purpose.

Social design is different, in that it separates the process of design from the artifacts it produces and applies it to complex social challenges at systems scale. Social design is the creation of new social conditions in cities, corporate cultures, communities, or teams with the intended outcomes of deeper civic or cultural engagement and increased creativity, resilience, equity, social justice, and human health. Along the way to these new social conditions, products and services are often developed, but they are the means to an end, part of a larger system that includes invisible social dynamics as well as artifacts.

Among the many people working to address social issues of health equity, the question inevitably arises—how social design is different from what they already do? We have tried to address those questions in practical terms throughout this site.

The System

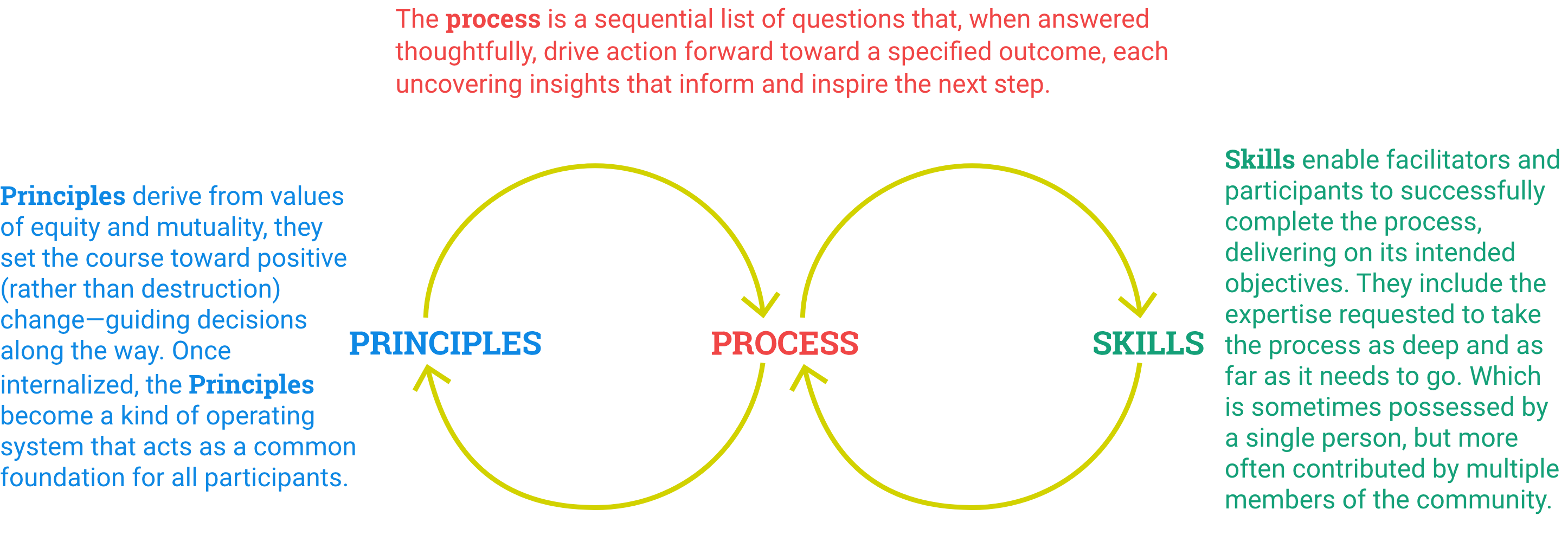

Social design is comprised of a set of principles, a process for organizing actions that propel progress from one stage to the next, and a specific set of skills required for the successful application of the principles and navigation of the process. Each component of the system of social design plays a distinct role, and there is a causal, symbiotic relationship between them.

Process is a sequential list of questions that, when answered thoughtfully, drive action forward toward a specified outcome, each uncovering insights that inform and inspire the next step.

Principles derive from values of equity and mutuality. They set the course toward positive (rather than destruction) change—guiding decisions along the way. Once internalized, the principles become a kind of operating system that acts as a common foundation for all participants.

Skills enable facilitators and participants to successfully complete the process, delivering on its intended objectives. They include the expertise requested to take the process as deep and as far as it needs to go. Skills are sometimes possessed by a single person but more often contributed by multiple members of the community.

The Components

Vision: The ultimate purpose which includes social, environmental and financial value

Mapping: Scoping of the entire system that is impacted by or is part of the system or problem

Human-Centered Research: Participatory investigation from the point of view of the people affected

Problem Reframing: Identifying the most upstream point in the system and finding new perspectives that inspire novel thinking

Idea Development: An iterative process connected to research and prototyping

Prototyping: Experimenting with ideas and representing them in order to allow audiences to experience them before implementation

Measuring: Integrated throughout the process

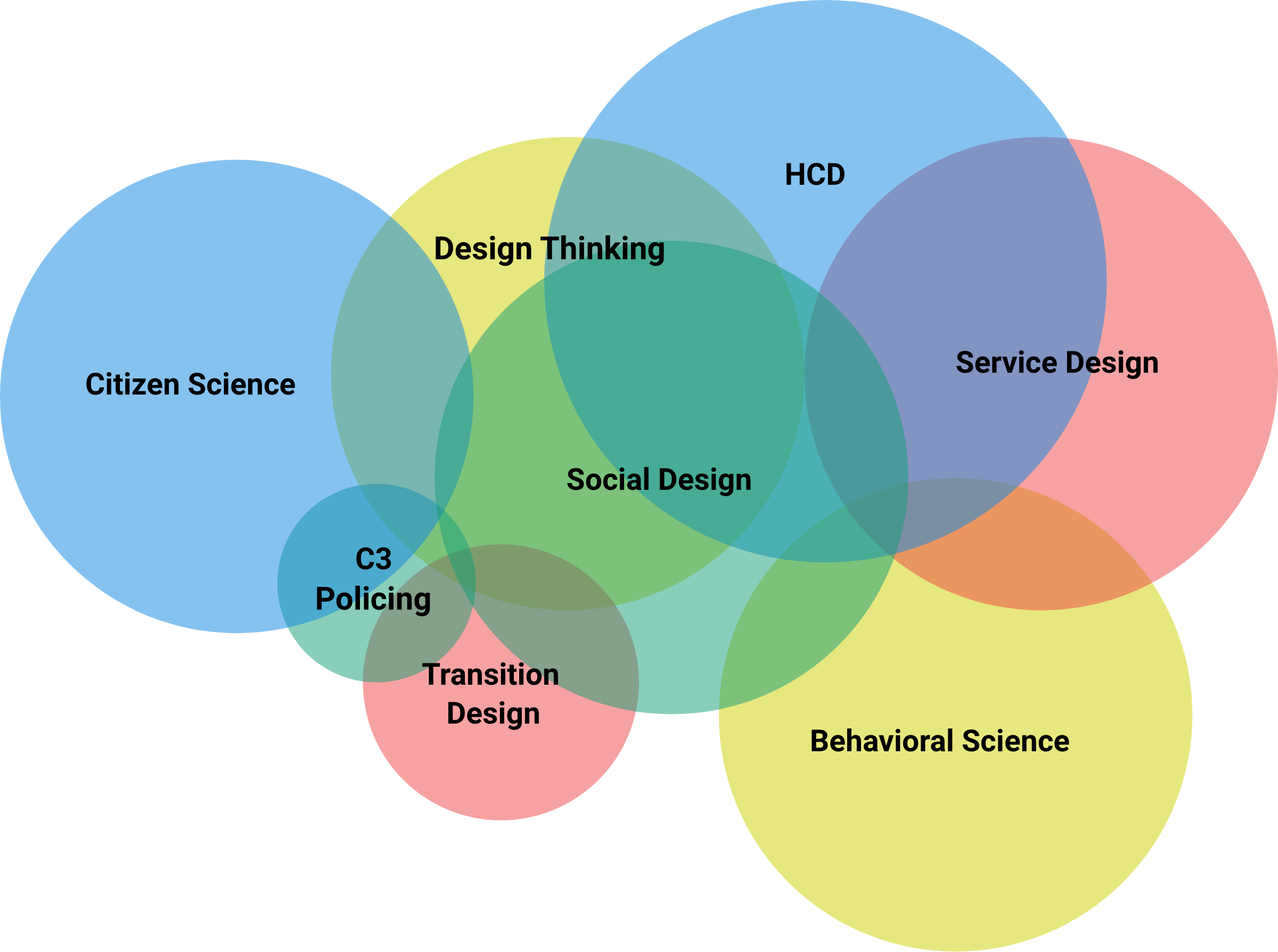

Social design in relation to other methods

The distinctions between related practices used to improve human health are fluid and can be confusing. Many of the principles, process steps, and skills used in social design show up in neighboring disciplines, such as collaborative research methods, problem reframing, idea generation, and prototyping. Rather than seeing them as contradictory, this reflects the potential for broader collaboration.

Decoding the Language

Social design thrives on collaboration between diverse partners: scientists, designers, health workers, NGOs, funders, and local communities around the world. Despite the amount of progress we are making to work together, we still do not have a shared language to concretely describe our practices, which would facilitate that collaboration. Perhaps we never will. We have different words to label similar things, like HCD, design thinking, relational design, impact design, service design, and social design; we label people we are serving as end users, stakeholders, actors, community, or patients. We sometimes use words interchangeably that are not, like prototype, pilot, test, or proof of concept. We are all guilty at times of using words vaguely and speaking in generalities about implementation, outcomes, or scale. Often, we use the same words to mean different things, such as research or impact. Certain disciplines feel so strongly about their “ownership” of these words and their right to use them based on the rigor of their practice that they don’t think other disciplines should be allowed to use them.

We do not yet have the words to describe the kind of information and feedback that propels the design process, the kind of evidence that is not data and not countable. This is a new frontier in measurement—the difference design makes and how it works.

Of course, we will never influence the millions of people working in these overlapping disciplines to use the same language to describe what they do. It is the nature of every discipline to develop jargon that acts as shorthand between its members. All we can attempt here is to highlight and define the words various disciplines use. Because we view language as a critical component of collaboration and collaboration between different practices so essential to social design, we will continue to add to what’s here in an effort to untangle, illuminate, and align.

Link to MeasureD Glossary of Terms

The Role of Measurement

The social design cases reviewed on the MeasureD site integrated measurement into their approach or practice in a variety of ways. Based on their experience, we chose to frame the use of measurement according to the intended purpose and the stage at which measurement was employed. Key terms associated with measurement practice are found here.

Measurement integrated during the design process, to inform design research, shape emergent ideas, eliminate and prioritize ideas, and co-create, test, and refine solutions

Measurement approaches during design are similar to traditional formative research but can also be less structured and formalized. The use of a protocol is not common, but gathering information is purposeful. It is not unstructured or random. Data collection is defined by the overall intent of the social intervention and focused on gaining insights that help frame (or reframe) the problem from the user perspective and contextualize the problem in communities, facilities, institutions, societies, etc.

Data collection methods are mainly qualitative, though design can draw on existing qualitative or quantitative data related to the context, the problem, and the people under study. Examples of data collection methods include in-depth interviews and focus group discussions with end users, key stakeholders and influencers; observation of users; experiential techniques such as journey mapping or process mapping; and the use of interactive techniques such as games, card sorting, etc.

There is no ideal or recommended sample size of respondents or participants in the immersion or co-creation processes, but the number of respondents or participants is often small compared to traditional research approaches. Designers choose respondents based on their relationship to the social impact intent and those at the heart of experiencing the problem. At minimum, respondents include the “end user” and often engage all stakeholders who will be affected by the intervention: people linked to the end user and their experience (based on the intent/BUILT focus), those who might influence the opinions and behavior of the end user, those working in the services that end- users frequent; and those that define social and/or political norms in which the end user lives.

Data and observations are analyzed and synthesized by designers in order to:

- Understand the problem and frame it, from the user perspective

- Define different types of users and their relevance to the problem

- Understand the context and how it influences user opinions and experience

- Eventually suggest a range of possible solutions to the problem through divergent and convergent thinking and co-creation processes with end users and stakeholders

During co-creation, which involves developing, testing, and refining prototypes of different possible solutions, designers gather data on end users interaction with and reaction to prototypes, as well as reflection with stakeholders to form judgments on the desirability, feasibility, and viability of different solutions.

Designers often report findings in the form of visual representations of insights, findings, and solutions rather than text-based reports. Often, because these findings or collections of evidence are not captured in traditional data, they can seem less factual or scientific. That does not mean that they don’t represent significant information that the designer uses throughout the process to refine and redirect solutions.

All MeasureD cases practice this kind of “measurement.”

Measurement as part of the intervention to enable implementers and end users to test theories of change or as part of the implementation strategies that were defined at the design stage and assess the effectiveness of the intervention.

Data is collected in a deliberate way, using routine tracking of defined programmatic metrics or focused deep-dives to explore hypothesized pathways of change that are expected to lead to program outcomes. Data collection approaches often involve a mix of qualitative and quantitative strategies to create a full picture of program experience, and to explore the relationship between the intervention and proposed changes in service coverage and quality; uptake of services, behaviors or products; and end users perceptions of a service or product.

Specifically, designers and implementers use data to track the effectiveness of intervention strategies in reaching both intermediate outcomes or ultimate outcomes. They can explore and interpret data during implementation for the purpose of adapting and improving the intervention in order to address gaps in effectiveness or confirm the effectiveness of implementation strategies. In those cases, data or measurement becomes a driver of change alongside other program practices (such as participation, management, and service delivery) to enable continuous quality improvement and inform strategy. Data collection, interpretation, and use mimic the iterative processes used in design and are often described as adaptive management, developmental evaluation, collaborative learning, or quality improvement cycles. Measurement also provides a focal point for implementers and teams to define shared concepts of success and to come together to rethink strategies if progress is lacking.

Analysis, interpretation, and learning take place periodically as part of the implementation process. Dashboards or other visualization tools for exploring data are common. Routine program team meetings or reflection points that aggregate all data and learning (objective and subjective) are required to optimize the value of measurement in this process. MeasureD cases that practice this form of measurement: Built for Zero; A360; Fitwits; MomsConnect; Greater Goods; Benefits Access; NYC Mayor’s office (forthcoming); C3; and Mass Design.

Measurement of the effectiveness of the intervention to assess the extent to which the social design intervention has been effective in achieving impact.

Known as traditional program or impact evaluation, measurement focuses on assessing the relationship between the intervention (that was created using social design) and the intended social outcome (improved health, reduced prevalence of homelessness, improved services, etc.). Researchers or evaluators work with program implementers and stakeholders to define a rigorous evaluation strategy based on the intervention theory of change, employing both quantitative and qualitative research methods to collect and analyze data, testing proposed program theory. Evaluators use standardized approaches or experimental or quasi-experimental research designs that allow statistical analysis and tests to assess the significance or strength of the relationship between the intervention and the outcome (attribution). In many cases, researchers add qualitative methods to explain or explore quantitative findings or use a true mixed methods approach that integrates qualitative and quantitative methods to explore the main research questions and add strength, depth, and context to the analysis and reveal opportunities to explore inconsistent findings. In those cases, social design is considered alongside other programmatic design choices and drivers of performance as part of the overall program strategy.

MeasureD cases that have or are planning to practice this form of measurement include A360 and C3 Policing.

Measurement of the influence of social design on program implementation strategies, social outcomes, and the behavior of implementers and humans in order to generate evidence of the contribution of design to social impact.

The focus of measurement is to unpack the relationship between the use of social design and program practice and outcomes. Social design is a new practice. Designers, implementers and funders lack documentation and evidence of how design works in practice, and how and where design adds value to social impact programs and outcomes. Questions include: Does design influence or contribute to the focus of an intervention, intervention strategies, implementer behavior, and especially social impact? If so, how? How does design compare to traditional program design and implementation approaches? Can you isolate the influence of design from other programmatic elements? Research or writing that explore these questions currently exists in the form of self-reported experience and observation, mixed methods descriptive, exploratory case studies, and early studies that are currently at the mid-phase of implementation.

MeasureD cases that have or are planning to practice this form of measurement include A360 and NYC Mayor’s office (forthcoming).