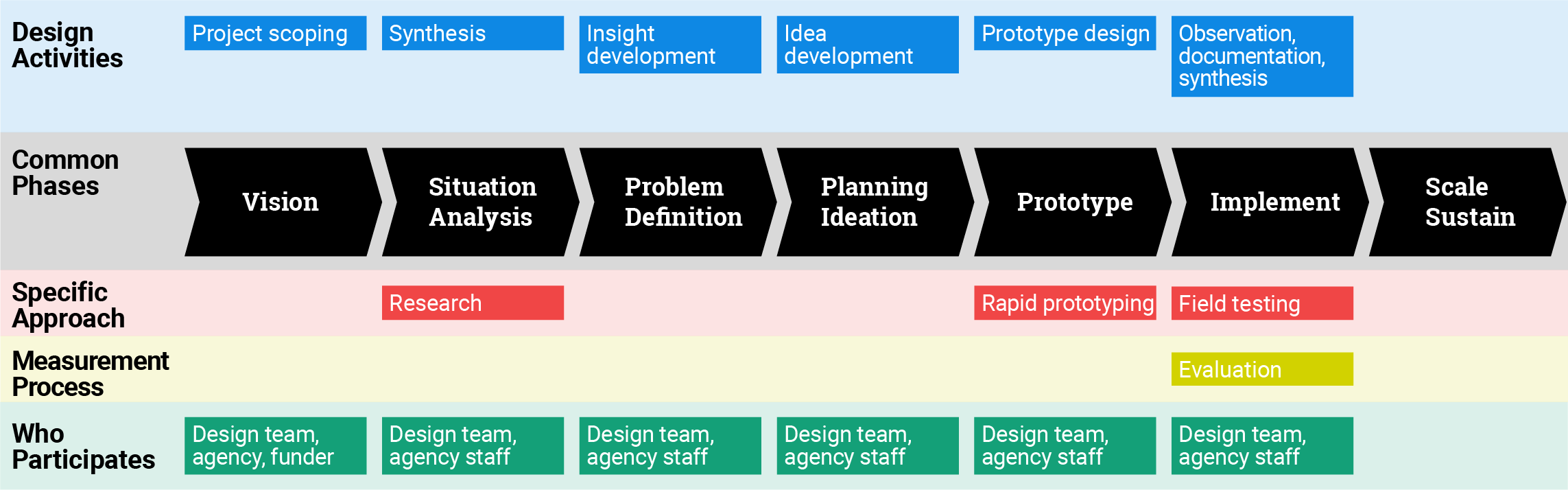

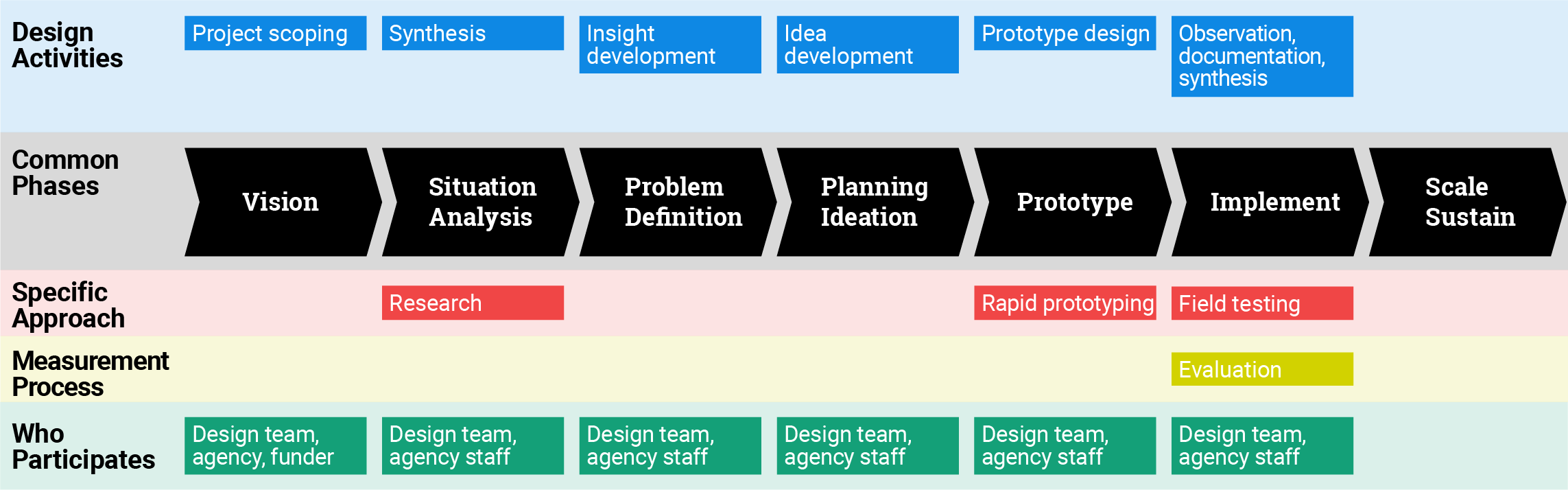

Amount of Design: End to End

Phase 1 – Proof-of-Concept

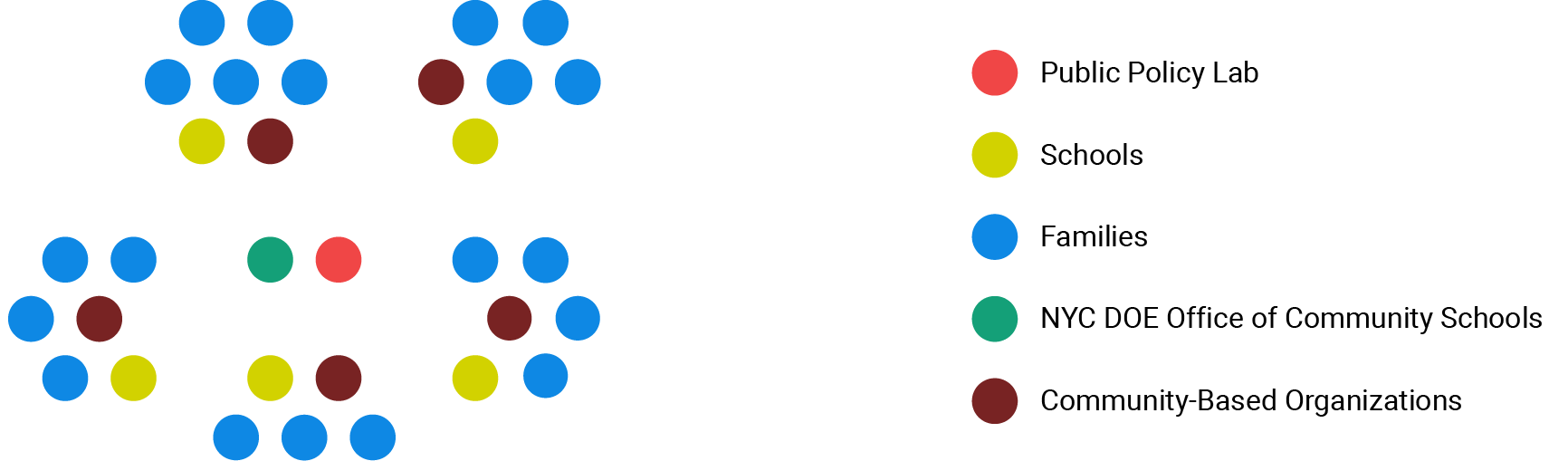

In Phase 1, a proof-of-concept effort that lasted 16 weeks, the project team conducted research in five Community Schools, spending time with school staff to learn how they currently connect families to benefits. After synthesizing this research, the team focused on exploring five major design questions:

1. Will parents contact school staff if they’re informed about in-school benefit support?

2. Will school staff refer parents to the CBO office if they get help spotting students in need?

3. Can school staff connect parents and guardians to a benefits enroller by using an online screening and referral tool?

4. Is it effective for CBO staff to engage and screen family members at high-attendance school events?

5. If a benefits enroller holds regular ‘office hours’ at school, will parents and guardians attend and apply?

The team created protocols to test each question and asked staff at four schools to implement these protocols over three-week field test. They gave each school a set of designed outreach materials and a school-specific digital platform developed by Single Stop for screening and referrals. They created a pipeline in which school staff identified families in need and connected them to the in-school CBO office for benefits screening. The in-school CBO office then referred these families to an external CBO case worker who, instead of scheduling an appointment at an off-site location, met with them at the school to help them apply for benefits. The team tracked outcomes during this period using multiple qualitative and quantitative assessments.

From this field-test, the team discovered the following key learnings:

- Get the timing right. Work in public schools is driven by the 10-month school calendar. Any large-scale programmatic change should reflect this by allowing administration and school staff to plan and prepare for launch during lower-demand times of year. Based on PPL interviews with school staff, programs should be launched in either October or January to have maximum impact. Also, a pilot program designed to enroll parents in benefits should run for at least six months to allow parents time to navigate the process.

- Empower champions at multiple levels. A successful pilot initiative should be embraced and explicitly endorsed by school administration – likely an assistant principal who can represent the vision of the initiative, observe pilot activities, and troubleshoot as challenges arise. Just as important, a pilot should be managed day-to-day by a champion who has knowledge of benefits programs and regular contact with the relevant school and CBO staff. In many cases, the community school director would be the best champion for an initiative of this type.

- Allow for variation. Public schools vary greatly in terms of programmatic offerings, management dynamics, institutional partnerships, and staff capacity for extra-curricular responsibilities. A successful pilot initiative should recognize this variation, allowing the champions at the school level to customize the assignment of roles and responsibilities, the structure and content of communications campaigns, and the frequency of caseworker office hours.

Phase 2 – Pilot-Testing Strategy & Toolkit

In Phase 2, which lasted seven months, PPL expanded the intervention to a pilot with 21 Community Schools, in order to explore their hypothesis and design questions across a variety of school contexts and deepen their understanding of the barriers to benefits enrollment. The intended outcome of Phase 2 was replicable model and an associated set of tools or materials, pilot-tested in a variety of settings.

During discovery research, the team visited 21 schools across the Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens and talked to nearly 200 people—including community school directors, principals, guidance counselors, parent coordinators, teachers, school staff, and families.

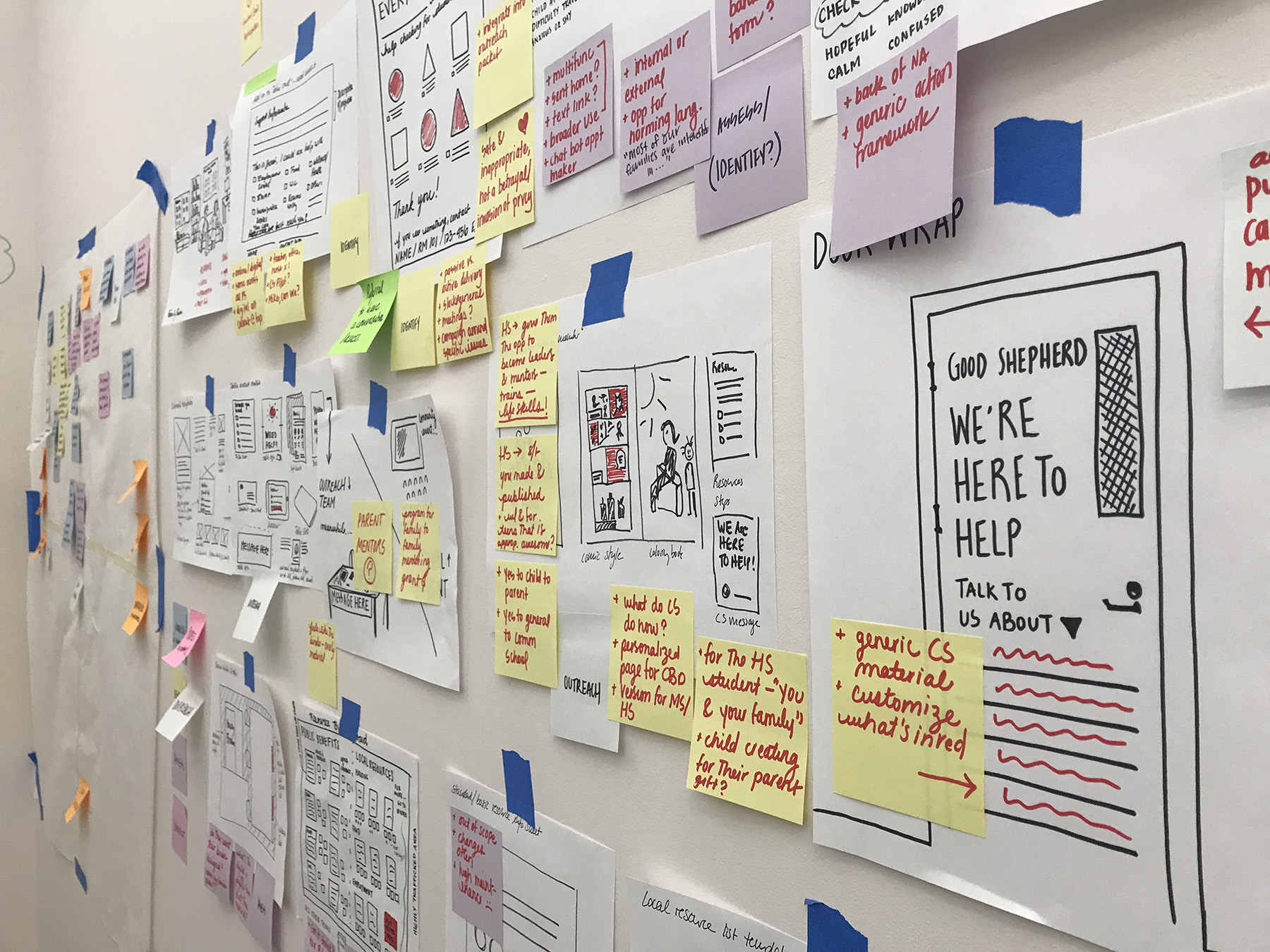

Following fieldwork, the team analyzed the rich information from our research by identifying which needs were shared among families and staff and what best practices were already in place. They observed that school staff move through similar steps when working with families to connect them to benefits and services—staff became aware of a family’s need, worked together to determine who in the school could best serve their need, and then did the necessary research to connect that family to a service provider. With this in mind, the team created a set of concepts—materials, tools, and processes to further explore and refine with staff and families.

They invited six schools to participate in co-design sessions and a two-week field test of the initial concepts. After the field test, the team refined the concepts into stand-alone prototypes and had all 21 schools test them during a four-week pilot period.

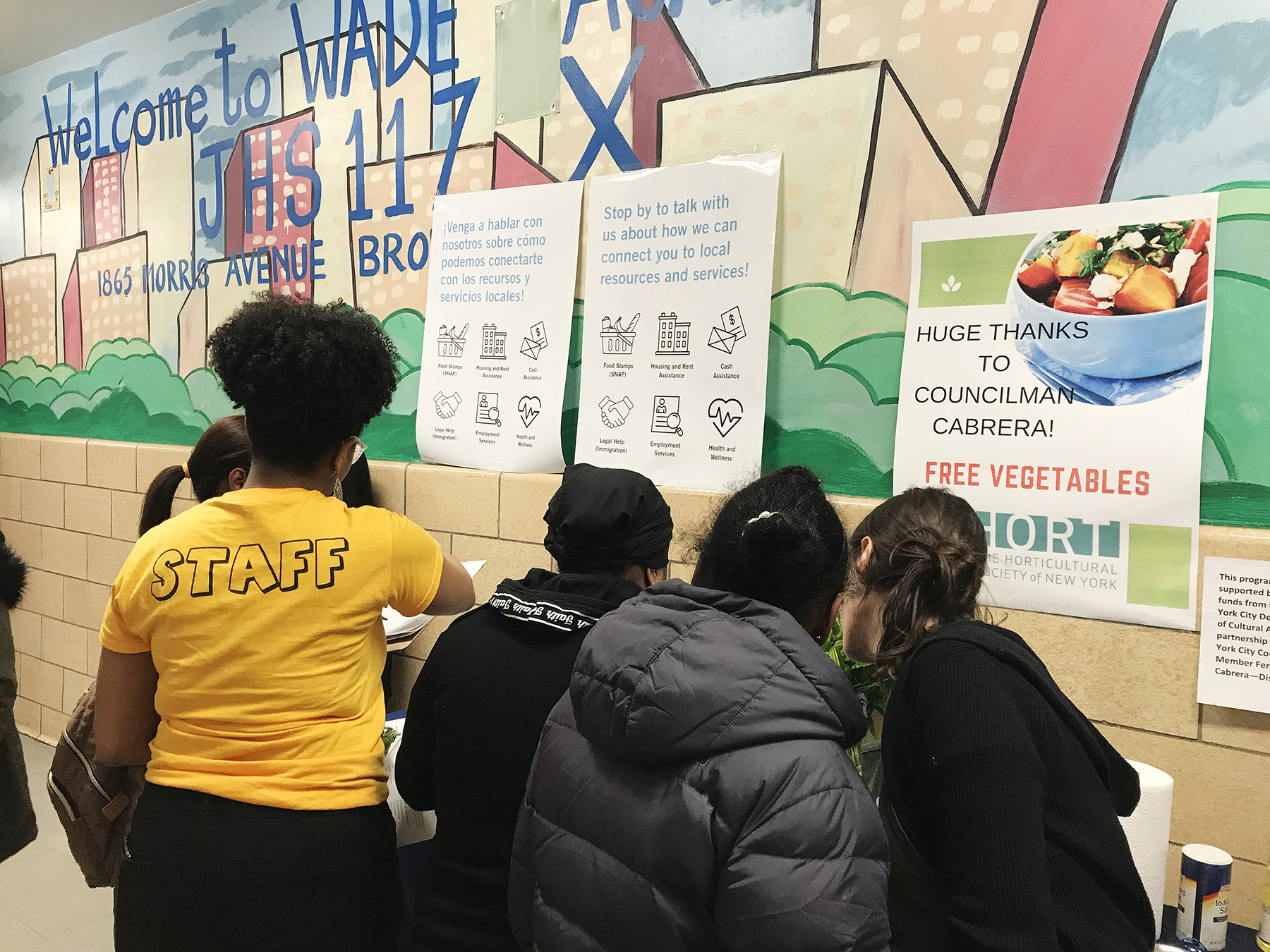

During this period, the team also attended six schools’ Community School Forums and conducted a total of 70 surveys and interviews with families. In these interactions, the team asked families which benefits and services they would like to access, whether they’d approached their school for benefits help, and what kind of support they would prefer. Families were most interested in housing, employment, and health benefits, and said they’d most appreciate help with referrals to organizations, figuring out their eligibility, and coaching on benefits applications. However, most had never reached out to school staff about benefits, either because they were not aware they could or because they didn’t feel comfortable asking for assistance.

After gathering feedback from participating pilot schools, PPL refined the tools once more and designed a final Benefits Access Strategy & Toolkit, which includes both a strategy that empowers staff to prepare, reach out, and connect families to benefits, and also a set of tools that staff can adapt for their school community context and team capacity.

The strategy is a three-phase approach that involves:

- preparing for and planning activities with a team,

- reaching out to families about benefits, and

- connecting families to benefits and following up with them about their experience.

The toolkit includes ten flexible tools designed to support school staff as they go through the three phases above. Both the strategy and toolkit amplify what schools are already doing to help families and build on the following principles:

- Understand Your School Community

- Integrate the Tools into Existing Workflows

- Distribute the Work

- Continue Building Trust with Families

Using the tools and approaches under the three phases, school staff can take a variety of paths to connect families with benefits, which range from simply providing families with information about benefits to having guided one-on-one meetings.

The long-term goal of Benefits Access is to increase 1) staff referrals to benefits and services and 2) family enrollment in those benefits and services. School staff can track these key metrics using tracking tools in the toolkit, including an Evaluation Worksheet that guides them through reviewing these metrics and making improvements to their strategy after each year.